Phylloxera

in ChampagnePhylloxera vastatrix (also known as Phylloxera vitifolii, Viteus vitifolii, Dactylosphaera vitifolii, Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) was introduced by experimental vines from the east coast of the USA via London to the south of France in the 1960s. By 1900, the majority of European vines (Vitis vinifera L.) were either infested or already destroyed. This devastating plague did not reach the Champagne region in the far north of the country until 1890. Initially, phylloxera was largely ignored in southern France. However, when phylloxera finally proved its truly terrifying destructive potential, every conceivable control method was tried. Even another species of louse (Tyroglyphus phylloxera), which is considered the arch-enemy of this phylloxera (but is harmless to vines), was imported. Unfortunately, this louse did not feel particularly at home in the European climate and proved to be useless. Treating the foliage with chemicals such as sulphure de carbone (hydrocarbon sulphide) appeared to have a promising effect, but ultimately also proved ineffective because it only effectively affected one stage of the phylloxera's complex life cycle. What the winegrowers did not realise at the time was that, in a practical sense, their infested vines were actually two types of phylloxera at the same time: leaf aphids (gallicola) and root aphids (radicicola).

What winegrowers discover in the foliage when their vines are infested is already an advanced stage of the phylloxera life cycle. These (leaf) aphids suck on the leaves and at the same time release their saliva into the sap ducts, which in turn causes outgrowths (galls) on the underside of the leaves. These small galls grow around the wingless aphids (gallicolae) with a small opening to the surface of the leaf. In these galls, the aphid lays several hundred tiny, lemon-coloured, oval eggs. After about eight days, new young aphids hatch from the eggs and continue to attack the foliage of the vine, forming galls again and laying more eggs. This part of the cycle produces three to six generations of phylloxera, primarily over the summer months. Finally, the leaves turn a lifeless brown colour and fall off. A proportion of the aphids on these leaves move on beforehand, while the others fall to ground level (at this stage the aphids are known as neogallicicolae-radicicolae).

Once there, they continue their activities on the root system (these aphids are now considered radicicolae). Such circumstances in the foliage must have annoyed the experienced winegrowers at the time, but certainly did not seem particularly worrying at first, as similar parasitic side effects in the cultivation of wine or even hops had long been known. What they didn't realise, however, was that even if this leaf phase of the phylloxera is rather insignificant, these young vine aphids had now also settled in the roots of their vines to overwinter there as pupae. In addition, the (root) phylloxera and the pupa are almost invisible, as they resemble the roots in colour and are also very small (0.7 - 1 mm). In spring, the vines revive seasonally, the pupae shed their skin, suck on the roots, form galls and lay eggs again. Three to six generations of Phylloxera also develop underground. Initially, the root system is not significantly damaged by the phylloxera. As soon as the end of summer approaches, some of the previously wingless phylloxera now grow wings. In autumn, they leave their underground home, infest the same vine above ground or migrate and fly to other vines, lay about 5 eggs somewhere near the ground on the vine or under the leaves of the now infested vines and die. The eggs laid are either small (male) or large (female). Approximately two weeks later, new aphids hatch, this time male and female. However, they are only intended for reproduction and have no organs for parasitic purposes. They mate, and the mother aphids now lay an olive-green or brown 'winter egg' (approx. 0.27 x 0.13 mm), usually hidden in slits in the bark of the vine. This egg either hibernates hidden in the bark, or a new (1 - 2 mm long) mother louse may hatch in the same year. This louse is considered to be the 'stem mother' (fundatrix) and turns to the fresh foliage of the vine, thus forming a gall where hundreds of eggs are laid. These then develop into (leaf) aphids and the cycle repeats itself. After two to three years, the vine dies (primarily due to root damage) and any remaining aphids move on to the next vine

If a winegrower discovers leaf symptoms, this generally means that neighbouring vines have probably already been infested for a long time. Clearing the infested vines, even down to root level, is generally useless. On the contrary: it can even encourage the spread of phylloxera, as it can be introduced into new regions via gaps and niches in tools and agricultural equipment (even through the boots of workers or even in baskets) when removing the bushes and roots, for example.

Phylloxera itself (without 'help' from humans) spreads rather slowly (approx. 25 - 30 km/year). The winged vine aphids generally only cover very short distances (with an optimal tailwind, however, 30 km are conceivable). The wingless aphids are also occasionally blown by the wind onto nearby vines. Aphids also migrate underground to intertwined roots of other vines. Climatically favourable conditions (warmer climate) promote the life cycle.

However, let us briefly return to the Champagne of the time. The cooler climate meant that phylloxera progress was slow at first. Winegrowers in Bordeaux, for example, were already well into the fight against phylloxera, which gave winegrowers in Champagne plenty of warning (and experience in combating it) in advance. So the plague was hardly 'unexpected' in Champagne. A meeting of all the winegrowers in Champagne was therefore held on 13 June 1891 in Epernay to face the new enemy together. However, the French musketeers' slogan 'one for all and all for one' had very little to do with the vineyard owners in Champagne. Of the 25,729 vineyard owners at the time, only 17,370 signed up to join the new 'Syndicat de Defénce'. The advance of phylloxera could therefore hardly be prevented by this incomplete syndicate, but it could still be slowed down somewhat. Someone in France had apparently realised in the meantime that the vines originally imported from the USA were thriving despite phylloxera, and that they were largely immune to phylloxera. It was therefore necessary to uproot the native vines, and as a result, rapid planting with phylloxera-resistant vine rootstocks from the USA, grafted with native vines, was the order of the day. Nevertheless, Phylloxera struck the ungrafted vines to an alarming extent. By 1910, half of the vineyards in the Marne region were already hopelessly infested with phylloxera.

There were and are therefore several options for winegrowers (not only) in Europe in terms of successfully combating phylloxera. By far the preferred solution in Europe was and is the use of rootstocks of phylloxera-resistant American grape varieties (e.g. Vitis riparia, rotundifolia, berlandieri, rupestris, lambrusca) with subsequent grafting of European Vitis vinifera L grape varieties (grafted vines). However, the different American rootstocks are said to have different quality and yields of vinifera fruit. According to a report in the Sonoma County Viticulture Newsletter, the leaves of the European Vitis vinifera L grape varieties are not particularly favoured by Phylloxera (see reference to the corresponding PDF file below).

Another solution was the cultivation of American vines (such as the well-known Noah and Isabella vines).

The American vines were also successfully crossed with European vines. This resulted in well-known hybrid varieties such as Baco, Delaware and Othello.

Phylloxera is historically regarded as the greatest misfortune of viticulture in France (or Europe). On the other hand, however, before this phylloxera, France was virtually flooded with numerous inferior grape varieties in often unfavourable locations. When replanting with new vines from the USA, the winegrowers made sure that only the best domestic grape varieties in their good locations received this considerable investment in labour and money for this grafting. Phylloxera also continues to be an international problem for winegrowers in Europe and many other countries (including, for example, on the west coast of the USA). In addition, the biology of phylloxera is still not fully understood. Even the famous NASA is concerned with this phylloxera. Frighteningly, there is now also talk of mutations. The battle against Phylloxera is therefore not even close to being won.

Back to the lexicon & glossary | You were here: Phylloxera

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Jouy-les-Reims-PLZ-51390.jpeg

375

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-22 09:12:262024-08-03 21:16:21Jouy-lès-Rheims

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Jouy-les-Reims-PLZ-51390.jpeg

375

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-22 09:12:262024-08-03 21:16:21Jouy-lès-Rheims champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BINET_Montagne_de_Reims.jpg

336

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 18:42:182024-08-03 21:17:37Reims

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/BINET_Montagne_de_Reims.jpg

336

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 18:42:182024-08-03 21:17:37Reims https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Epernay-PLZ-51200.webp

906

1360

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 18:30:232024-08-03 21:18:27Épernay

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Epernay-PLZ-51200.webp

906

1360

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 18:30:232024-08-03 21:18:27Épernay https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/INAO.jpg

675

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:56:042024-08-03 21:19:50INAO

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/INAO.jpg

675

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:56:042024-08-03 21:19:50INAO champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/alfred-gratien.jpg

1280

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:52:002024-08-03 21:22:10Historical grape varieties

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/alfred-gratien.jpg

1280

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:52:002024-08-03 21:22:10Historical grape varieties https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/hautvillers-champagne.jpg

960

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:48:202024-08-03 21:23:20Hautvillers

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/hautvillers-champagne.jpg

960

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:48:202024-08-03 21:23:20Hautvillers https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Haltbarkeit-und-Lagerung.jpeg

440

783

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:46:572024-08-03 21:24:14Shelf life and storage

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Haltbarkeit-und-Lagerung.jpeg

440

783

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 16:46:572024-08-03 21:24:14Shelf life and storage https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Grauves-PLZ-51190.jpg

768

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 13:40:432024-08-03 21:24:57Grey vines

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Grauves-PLZ-51190.jpg

768

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 13:40:432024-08-03 21:24:57Grey vines champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Champagner-H-Blin.jpg

1200

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 13:38:272024-08-03 21:28:31Champagne glasses

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Champagner-H-Blin.jpg

1200

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 13:38:272024-08-03 21:28:31Champagne glasses https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Flaschengaerung.jpg

800

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 00:03:282024-08-03 21:33:23Bottle fermentation

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Flaschengaerung.jpg

800

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-10 00:03:282024-08-03 21:33:23Bottle fermentation https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Flaschendruck.jpg

1125

2000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:40:192024-08-03 21:34:25Bottle pressure

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Flaschendruck.jpg

1125

2000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:40:192024-08-03 21:34:25Bottle pressure https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Fermentation.jpg

630

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:39:482024-08-03 21:36:08Fermentation

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Fermentation.jpg

630

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:39:482024-08-03 21:36:08Fermentation champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/billecart-salmon-champagner-extra-brut.png

600

600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:37:402024-08-03 21:37:45Extra Brut

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/billecart-salmon-champagner-extra-brut.png

600

600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:37:402024-08-03 21:37:45Extra Brut https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Etrechy-PLZ-51130.jpg

1024

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:35:582024-08-03 21:38:54Étréchy

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Etrechy-PLZ-51130.jpg

1024

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:35:582024-08-03 21:38:54Étréchy https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ecueil-PLZ-51500.jpg

367

550

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:35:182024-08-03 21:39:37Écueil

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ecueil-PLZ-51500.jpg

367

550

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:35:182024-08-03 21:39:37Écueil https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Doux-Champagner.webp

550

800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:34:152024-08-03 21:40:53Doux

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Doux-Champagner.webp

550

800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:34:152024-08-03 21:40:53Doux https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Dizy-PLZ-51530-scaled.jpeg

1707

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:33:182024-08-03 21:41:29Dizy

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Dizy-PLZ-51530-scaled.jpeg

1707

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:33:182024-08-03 21:41:29Dizy https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cumieres-PLZ-51480.jpg

900

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:31:292024-08-03 21:42:07Cumières

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cumieres-PLZ-51480.jpg

900

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:31:292024-08-03 21:42:07Cumières https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cuis-PLZ-51530.jpg

768

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:30:592024-08-03 21:42:45Cuis

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cuis-PLZ-51530.jpg

768

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:30:592024-08-03 21:42:45Cuis https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cote-des-Blancs.png

860

1300

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:28:302024-08-03 21:43:36Côte des Blancs

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cote-des-Blancs.png

860

1300

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:28:302024-08-03 21:43:36Côte des Blancs https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cote-des-Bar.png

1086

1407

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

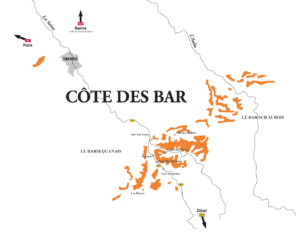

admin2021-01-09 23:27:552024-08-03 21:44:16Côte des Bar

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cote-des-Bar.png

1086

1407

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:27:552024-08-03 21:44:16Côte des Bar https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Coligny-PLZ-51130.jpg

1620

2160

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:26:312024-08-03 21:45:13Coligny

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Coligny-PLZ-51130.jpg

1620

2160

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:26:312024-08-03 21:45:13Coligny https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CIVC-comite-champagne.jpg

669

892

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:25:432024-08-03 21:46:22CIVC

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CIVC-comite-champagne.jpg

669

892

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:25:432024-08-03 21:46:22CIVC https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chouilly-PLZ-51530.jpg

665

1000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:24:202024-08-03 21:48:38Chouilly

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chouilly-PLZ-51530.jpg

665

1000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:24:202024-08-03 21:48:38Chouilly https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chlorose.jpg

491

873

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:12:392024-08-03 21:49:24Chlorosis

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chlorose.jpg

491

873

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:12:392024-08-03 21:49:24Chlorosis https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chigny-les-Roses-PLZ-51500.jpg

688

917

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:09:162024-08-03 21:50:24Chigny-les-Roses

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chigny-les-Roses-PLZ-51500.jpg

688

917

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:09:162024-08-03 21:50:24Chigny-les-Roses https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chaufferettes-Champagner.jpg

375

647

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:02:152024-08-03 21:54:32Chaufferettes

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chaufferettes-Champagner.jpg

375

647

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 23:02:152024-08-03 21:54:32Chaufferettes https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Champillon-PLZ-51160.jpg

1440

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:56:322024-08-03 21:55:46Champillon

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Champillon-PLZ-51160.jpg

1440

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:56:322024-08-03 21:55:46Champillon https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Moet-Chandon-Champagner-Kuebel.webp

800

800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:55:522024-08-03 21:56:36Champagne house

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Moet-Chandon-Champagner-Kuebel.webp

800

800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:55:522024-08-03 21:56:36Champagne house https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chamery-PLZ-51500.jpg

750

1050

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:55:072024-08-03 21:57:21Chamery

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Chamery-PLZ-51500.jpg

750

1050

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:55:072024-08-03 21:57:21Chamery https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Butte-de-Saran.jpg

600

900

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:54:462024-08-03 21:58:45Butte de Saran

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Butte-de-Saran.jpg

600

900

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:54:462024-08-03 21:58:45Butte de Saran https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Zero.jpg

834

1800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:53:442024-08-03 21:59:21Brut Zero

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Zero.jpg

834

1800

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:53:442024-08-03 21:59:21Brut Zero https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Non-Dosage.jpg

550

1170

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:52:462024-08-03 22:00:41Brut Non Dosage

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Non-Dosage.jpg

550

1170

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:52:462024-08-03 22:00:41Brut Non Dosage https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Nature.jpg

430

650

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:52:182024-08-03 22:01:25Brut Nature

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Brut-Nature.jpg

430

650

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:52:182024-08-03 22:01:25Brut Nature https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bouzy-PLZ-51150.jpg

683

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:51:302024-08-03 22:02:07Bouzy

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bouzy-PLZ-51150.jpg

683

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:51:302024-08-03 22:02:07Bouzy https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bisseuil-PLZ-51150.jpeg

182

278

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:50:442024-08-03 22:02:44Bisseuil

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bisseuil-PLZ-51150.jpeg

182

278

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:50:442024-08-03 22:02:44Bisseuil https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Billy-le-Grand-PLZ-51400.jpg

853

1280

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:49:492024-08-03 22:03:24Billy-le-Grand

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Billy-le-Grand-PLZ-51400.jpg

853

1280

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:49:492024-08-03 22:03:24Billy-le-Grand https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bezannes-PLZ-51430.jpg

720

960

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:48:342024-08-03 22:04:02Bezannes

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bezannes-PLZ-51430.jpg

720

960

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:48:342024-08-03 22:04:02Bezannes https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bergeres-les-Vertus-PLZ-51130.jpg

520

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:47:452024-08-03 22:04:41Bergères-lès-Vertus

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Bergeres-les-Vertus-PLZ-51130.jpg

520

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:47:452024-08-03 22:04:41Bergères-lès-Vertus https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Beaumont-sur-Vesle-PLZ-51360.jpg

644

997

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:46:562024-08-03 22:05:29Beaumont-sur-Vesle

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Beaumont-sur-Vesle-PLZ-51360.jpg

644

997

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:46:562024-08-03 22:05:29Beaumont-sur-Vesle champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/catter-champagner-blanc-de-noir.jpg

402

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:46:022024-08-03 22:07:33BdN

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/catter-champagner-blanc-de-noir.jpg

402

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:46:022024-08-03 22:07:33BdN https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:45:302024-08-03 22:08:25BdB

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:45:302024-08-03 22:08:25BdB https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ay-PLZ-51160.jpg

900

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:44:202024-11-04 13:07:13Ay

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ay-PLZ-51160.jpg

900

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:44:202024-11-04 13:07:13Ay https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Avize-PLZ-51190.webp

375

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:42:592024-08-03 22:09:42Avize

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Avize-PLZ-51190.webp

375

500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:42:592024-08-03 22:09:42Avize https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Avenay-PLZ-51160.jpg

499

752

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:42:262024-08-03 22:10:29Avenay

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Avenay-PLZ-51160.jpg

499

752

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:42:262024-08-03 22:10:29Avenay https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Autochthon-Champagner.jpg

1080

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:41:442024-11-04 13:04:05Autochthonous

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Autochthon-Champagner.jpg

1080

1920

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:41:442024-11-04 13:04:05Autochthonous https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Weinreben-Champagne.png

593

898

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:40:182024-11-04 12:59:36Arbane

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Weinreben-Champagne.png

593

898

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:40:182024-11-04 12:59:36Arbane https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ambonnay-PLZ-51150.webp

450

600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:38:102024-11-04 12:56:59Ambonnay

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Ambonnay-PLZ-51150.webp

450

600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:38:102024-11-04 12:56:59Ambonnay https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:37:022024-11-04 12:54:00Astringency

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:37:022024-11-04 12:54:00Astringency https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/A-la-volée.jpg

900

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:36:282024-08-03 22:12:33A la volée

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/A-la-volée.jpg

900

1600

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:36:282024-08-03 22:12:33A la volée champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/champagner-schauer.jpg

900

1500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:35:482024-11-04 12:51:44Dégorgement à la Glace

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/champagner-schauer.jpg

900

1500

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:35:482024-11-04 12:51:44Dégorgement à la Glace https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:34:422024-08-03 22:14:22Champagne bottles

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:34:422024-08-03 22:14:22Champagne bottles https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/champagner-korken.jpg

787

1181

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:25:422024-08-03 22:15:15Cork

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/champagner-korken.jpg

787

1181

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:25:422024-08-03 22:15:15Cork https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Viticulture.jpg

1707

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:24:032024-08-03 22:15:56Viticulture

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Viticulture.jpg

1707

2560

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:24:032024-08-03 22:15:56Viticulture https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:23:312024-08-03 22:16:35Viniculture

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:23:312024-08-03 22:16:35Viniculture https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:22:362024-08-03 22:17:47Vin Gris

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:22:362024-08-03 22:17:47Vin Gris https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:22:052024-08-03 22:18:23Vignoble

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:22:052024-08-03 22:18:23Vignoble https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:13:582024-08-03 22:18:54Vigne

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:13:582024-08-03 22:18:54Vigne https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Vieilles-Vigne.jpg

638

850

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:12:422024-08-03 22:19:29Vieilles Vignes

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Vieilles-Vigne.jpg

638

850

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:12:422024-08-03 22:19:29Vieilles Vignes https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Veuve-Clicquot-1950.jpg

1674

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

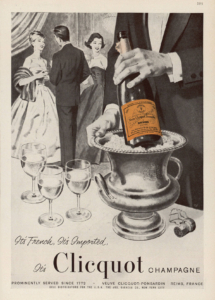

admin2021-01-09 22:11:442024-08-03 22:20:57Veuve Clicquot

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Veuve-Clicquot-1950.jpg

1674

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:11:442024-08-03 22:20:57Veuve Clicquot https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Ferdinand-Bonnet-Champagner-Weinlese.webp

1298

1304

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:10:312024-08-03 22:21:39Vendange

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Ferdinand-Bonnet-Champagner-Weinlese.webp

1298

1304

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:10:312024-08-03 22:21:39Vendange https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Traubensorten-Champagner.jpeg

453

893

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:09:592024-08-03 07:17:50Grape varieties

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Traubensorten-Champagner.jpeg

453

893

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:09:592024-08-03 07:17:50Grape varieties https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:09:052024-08-03 22:22:26Terroir

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:09:052024-08-03 22:22:26Terroir https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:08:252024-08-03 07:08:09Tannin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:08:252024-08-03 07:08:09Tannin https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:07:392024-08-03 22:23:20Waist

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:07:392024-08-03 22:23:20Waist https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:06:562024-08-03 07:04:23Tâché

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:06:562024-08-03 07:04:23Tâché https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:06:172024-08-03 07:02:14Sparkling wine

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:06:172024-08-03 07:02:14Sparkling wine https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:05:402024-08-03 22:24:52Sec

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:05:402024-08-03 22:24:52Sec https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:05:032024-08-03 22:25:27Ship christening

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:05:032024-08-03 22:25:27Ship christening https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:01:372024-08-03 22:32:00Prosecco

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:01:372024-08-03 22:32:00Prosecco https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Asti-Spumante.jpg

408

1300

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:01:002024-11-04 13:01:26Asti Spumante

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Asti-Spumante.jpg

408

1300

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 22:01:002024-11-04 13:01:26Asti Spumante https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/schaumwein.jpg

809

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:59:092024-08-03 22:35:14Sparkling wine

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/schaumwein.jpg

809

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:59:092024-08-03 22:35:14Sparkling wine https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:58:032024-08-03 22:39:34Acid

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:58:032024-08-03 22:39:34Acid https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:57:232024-08-03 22:41:08Sans-année

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:57:232024-08-03 22:41:08Sans-année https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Saint-Evremond.jpg

512

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:56:482024-08-03 02:30:20Saint-Evremond

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Saint-Evremond.jpg

512

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:56:482024-08-03 02:30:20Saint-Evremond https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/gyropalette.webp

347

576

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:56:022024-08-03 01:43:33Vibrating desk

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/gyropalette.webp

347

576

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:56:022024-08-03 01:43:33Vibrating desk https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:54:082024-08-03 01:32:17Shake

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:54:082024-08-03 01:32:17Shake https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Ruinart-Champagner.jpg

630

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:53:082024-08-03 01:07:39Ruinart

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Ruinart-Champagner.jpg

630

1200

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:53:082024-08-03 01:07:39Ruinart https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:52:162024-08-03 01:05:23Rosé des Riceys

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:52:162024-08-03 01:05:23Rosé des Riceys champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/besserat-de-bellefon-champagner-rose.jpg

1081

1812

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:51:352024-08-03 01:03:32Rosé

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/besserat-de-bellefon-champagner-rose.jpg

1081

1812

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:51:352024-08-03 01:03:32Rosé https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/louis-roederer.jpg

447

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:50:302024-08-03 01:01:51Roederer

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/louis-roederer.jpg

447

1440

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:50:302024-08-03 01:01:51Roederer https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:49:552024-08-03 00:58:57Residual sugar

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:49:552024-08-03 00:58:57Residual sugar https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:49:102024-08-03 00:39:59Remueur

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:49:102024-08-03 00:39:59Remueur https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:48:302024-08-03 00:38:14Réduction François

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:48:302024-08-03 00:38:14Réduction François https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:47:512024-08-03 00:36:10Récoltant-Manipulant (R.M.)

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:47:512024-08-03 00:36:10Récoltant-Manipulant (R.M.) https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:47:152024-08-03 00:20:47Récolte

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:47:152024-08-03 00:20:47Récolte https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:46:222024-08-03 00:19:27Phylloxera

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:46:222024-08-03 00:19:27Phylloxera https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:45:162024-08-03 00:17:41Rebêche

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:45:162024-08-03 00:17:41Rebêche https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:44:042024-08-03 00:15:58Ratafia de Champagne

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:44:042024-08-03 00:15:58Ratafia de Champagne https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:42:382024-08-03 00:14:18Rappen

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:42:382024-08-03 00:14:18Rappen https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:41:332024-08-03 00:12:33Pressoir

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:41:332024-08-03 00:12:33Pressoir champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/domaine-pommery.jpg

760

1360

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:40:272024-08-03 00:11:00Pommery

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/domaine-pommery.jpg

760

1360

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:40:272024-08-03 00:11:00Pommery champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/coulournat-gilles-champagne.png

700

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:39:232024-08-03 00:09:16Placomusophilia

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/coulournat-gilles-champagne.png

700

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:39:232024-08-03 00:09:16Placomusophilia https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Capsules-Muselets-Plaque-Champagner-Deckel.jpg

462

960

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:37:312024-08-03 00:07:34Plaque

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Capsules-Muselets-Plaque-Champagner-Deckel.jpg

462

960

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:37:312024-08-03 00:07:34Plaque champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/canard-duchene-champagner-pinot-noir.jpg

514

570

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:36:412024-08-03 00:06:26Pinot Noir

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/canard-duchene-champagner-pinot-noir.jpg

514

570

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:36:412024-08-03 00:06:26Pinot Noir https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:35:442024-08-03 00:03:53Pinot Meunier

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:35:442024-08-03 00:03:53Pinot Meunier https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:35:062024-08-03 00:01:58Pinot Gris

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:35:062024-08-03 00:01:58Pinot Gris https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:34:052024-08-02 23:58:02Pétillant

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:34:052024-08-02 23:58:02Pétillant https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:32:582024-08-02 23:54:36Perlant

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:32:582024-08-02 23:54:36Perlant https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:30:062024-08-02 23:53:04Oxidation

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:30:062024-08-02 23:53:04Oxidation https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:29:372024-08-02 23:51:15Oxhoft

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:29:372024-08-02 23:51:15Oxhoft https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:28:452024-08-02 23:49:26Ouverture des Vendanges

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:28:452024-08-02 23:49:26Ouverture des Vendanges https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:28:082024-08-02 23:43:48Oenology

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:28:082024-08-02 23:43:48Oenology https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:26:362024-08-02 23:42:34Öchsle

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:26:362024-08-02 23:42:34Öchsle https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:25:192024-08-02 23:40:34Négociant

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:25:192024-08-02 23:40:34Négociant https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Nase-Champagner.jpeg

1125

2000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:24:322024-08-03 01:45:19Nose

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Nase-Champagner.jpeg

1125

2000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:24:322024-08-03 01:45:19Nose https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:23:042024-08-02 23:34:13N.V.

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:23:042024-08-02 23:34:13N.V. https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Agraffe.jpg

600

900

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:21:572024-08-02 23:24:29Muselet

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Agraffe.jpg

600

900

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:21:572024-08-02 23:24:29Muselet https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Mumm-Champagne.jpg

1080

1080

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:16:082024-08-03 06:21:54Guts

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Mumm-Champagne.jpg

1080

1080

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:16:082024-08-03 06:21:54Guts https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:12:532024-08-03 06:18:34Moût

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:12:532024-08-03 06:18:34Moût https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:12:092024-08-03 06:16:56Mousseux

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:12:092024-08-03 06:16:56Mousseux https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:11:112024-08-03 06:17:51Mousse

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:11:112024-08-03 06:17:51Mousse https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:10:222024-08-03 06:23:34Mono-Cru

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 21:10:222024-08-03 06:23:34Mono-Cru https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:52:522024-08-03 06:24:42Méthode Champenoise

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:52:522024-08-03 06:24:42Méthode Champenoise https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:51:542024-08-03 06:25:34Marc

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:51:542024-08-03 06:25:34Marc https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:51:142024-08-03 06:26:28Maie

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:51:142024-08-03 06:26:28Maie https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:50:222024-08-03 06:28:08Malolactic fermentation

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:50:222024-08-03 06:28:08Malolactic fermentation https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Maceration.jpg

667

1000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:49:422024-08-03 06:32:21Maceration

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Maceration.jpg

667

1000

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:49:422024-08-03 06:32:21Maceration https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:49:092024-08-03 06:33:53Long

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:49:092024-08-03 06:33:53Long champagner.eu

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Liqueur-de-tirage.jpg

334

750

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:48:332024-08-01 03:10:50Liqueur de tirage

champagner.eu

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Liqueur-de-tirage.jpg

334

750

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:48:332024-08-01 03:10:50Liqueur de tirage https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:47:302024-08-03 06:34:55Liqueur d'expédition

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:47:302024-08-03 06:34:55Liqueur d'expédition https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:45:312024-08-03 06:35:56Read

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:45:312024-08-03 06:35:56Read champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/KRUG-CHAMPAGNE.png

350

350

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:43:552024-08-01 03:08:43Krug

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/KRUG-CHAMPAGNE.png

350

350

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:43:552024-08-01 03:08:43Krug https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:42:242024-08-03 06:37:45Body

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:42:242024-08-03 06:37:45Body https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:41:462024-08-03 06:38:42Cork flavour

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:41:462024-08-03 06:38:42Cork flavour https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:40:272024-08-03 06:39:40Carbon dioxide

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:40:272024-08-03 06:39:40Carbon dioxide https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Kirchenfenster-Champagner.webp

430

430

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:39:302024-08-03 08:04:14Church windows

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Kirchenfenster-Champagner.webp

430

430

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:39:302024-08-03 08:04:14Church windows https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:38:222024-08-03 06:40:30Pressing

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-09 20:38:222024-08-03 06:40:30Pressing champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ruinart-champagne.png

700

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:37:072024-08-03 07:01:13Champagne capsule

champagne.com

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ruinart-champagne.png

700

700

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:37:072024-08-03 07:01:13Champagne capsule https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Jahrgangschampagner.webp

538

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:34:592024-08-01 03:01:09Vintage champagne

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Jahrgangschampagner.webp

538

1024

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:34:592024-08-01 03:01:09Vintage champagne https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:33:352024-08-03 06:41:51Wood

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:33:352024-08-03 06:41:51Wood https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:32:402024-08-03 06:42:50Heidsieck

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:32:402024-08-03 06:42:50Heidsieck https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:31:362024-08-03 06:43:55Habillage

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:31:362024-08-03 06:43:55Habillage https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/gyropalette.webp

347

576

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:31:002024-08-03 06:45:26Gyro palette

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/gyropalette.webp

347

576

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:31:002024-08-03 06:45:26Gyro palette https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:30:232024-08-03 06:46:27Grappillage

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

admin2021-01-08 22:30:232024-08-03 06:46:27Grappillage https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png

1

1

admin

https://champagner.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Champagner.com-Logo-300x300.png